China is a country of superlatives.

It has world's largest group of life-sized statues, the world's largest science museum, the world's largest palace. Heck, it even has a wall that's visible from space.

It's the most populous country in the world.

And it's also the world's largest emitter of CO2.

But – bearing in mind that last one – perhaps thankfully, it's well on its way to becoming the world's renewable energy superpower.

The background

China's remarkable recent economic growth has lifted the country out of poverty, turning it into a leader in many industries but also the world's largest carbon emitter, accounting for one-third of global CO2 emissions.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), currently one of every four tons of coal used globally, is burned to produce electricity in China – an indicator of why the country tops the CO2 emissions charts.

But the government wants to change that and in September 2020 President Xi Jinping announced China will "aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060."

Of all the pledges from all the governments around the world, none is as important as China's and the country's ability reduce its emissions will be a crucial factor in global efforts to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

While there has been a determined push towards using gas in industrial and residential sectors, China's coal-fired power stations are young and highly efficient, and the fleet is still ten times larger than its gas-fired fleet.

New onshore wind and solar farms can in fact generate electricity far cheaper than new combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGTs), which - as is the case elsewhere - are increasingly being used to aide and support the integration of renewables.

With demanding emissions targets, coupled with the fact that energy sector is the source of almost 90% of China's greenhouse gas emissions, the manner in which China produces its energy for its power-hungry industry and ever-growing population is at the heart of the country's transition to carbon neutrality.

China's greener future

China's industrial footprint, its aspirational energy mix and its emissions targets makes for a heady brew.

Coal still accounts for over 60% of China's electricity generation and the country is actually still building new coal power stations.

But at the same time, China's has topped the renewables global leaderboard for years, adding more renewable power capacity than any other country year after year.

It's also the second largest oil consumer in the world.

But it's also home to 70% of global manufacturing capacity for electric vehicle batteries.

China has a massive population, an equally massive predicted growth and an accompanying huge forecasted demand for power.

It has also set itself on a decarbonisation pathway with stringent emissions targets.

So, the direction of travel is undeniable and well-justified. But with coal still accounting for so much of China's existing energy mix, exactly where is this new capacity going to come from?

Hydro

As things stand, hydro is China's biggest source of renewable energy. Statistics from 2021 reveal China's hydro power capabilities accounted for:

- 16% of its total power generation

- 58% of its total power generated from renewables

- 29% of all global hydropower capacity

- 80% of all new hydropower capacity added globally

And China is constantly adding to this impressive output.

In 2021 China installed 20GW of new hydro power capacity to reach 391GW of total hydropower capacity by year end, produced by around 1,000 hydro power plants across the country.

Most Chinese hydropower development is in the western and southern parts of the country with very little in northern China. The Three Gorges Dam, which became fully operational in 2012, is the world's largest dam with an installed capacity of 22.5GW.

The dam spans the Yangtze River and consists of 32 turbine-generator units, each with a capacity of 700MW, and is capable of generating approximately 101.6TWh of electricity per year.

The Three Gorges Dam is also the largest power station of any kind in the world, surpassing even the largest thermal power plants. It is a key part of China's efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and to meet its growing demand for electricity.

The Chinese government continues to support hydropower development, but capacity additions have slowed during the past 10 years.

The government's 14th Five-Year Plan for Renewable Energy - a set of economic goals designed to strengthen the Chinese economy between 2020 and 2025 - calls for hydropower to provide 17.4% of China's electricity generation in 2025 and "scientific and orderly" development of hydropower resources. (the plan gives more attention to solar and wind power than hydropower).

Wind power

The latest figures from energy think tank Ember say the global wind capacity will double by 2030 and the primary driver will be China, with expectations the country will install more than 50% of global wind additions between 2024 and 2030.

Ember also states China is likely to almost triple wind its capacity from 2022 to 2030.

With this for context it's no surprise that China leads the world in wind power, already accounting for more than one-third of global capacity. In fact, so fast is the growth of Chinese wind power that it will soon outstrip hydro.

According to Ember, in March 2024 China's wind farms produced over 100TWh of electricity, the highest monthly total ever by a single country and as much as all of Europe and North America combined.

China's output total in March was more than twice the generation in the US, the second largest wind producer, and nearly nine times more than produced in Germany, the number three producer.

Wind power's role in the production of China's electricity is increasing steadily, to an average of 11.4% during the first quarter of 2024 from 9.6% during all of 2023, rapidly catching up on hydro.

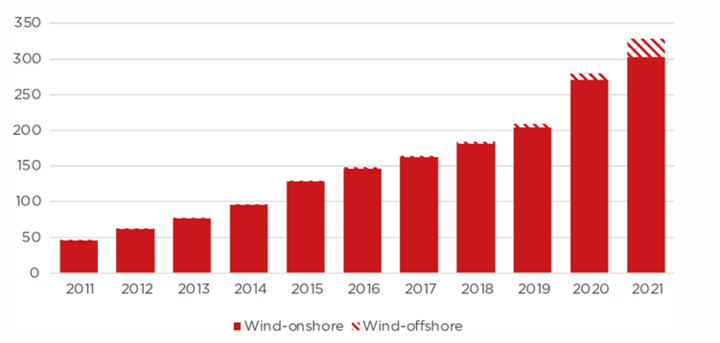

In 2021:

- roughly 48GW of wind power capacity was added to the grid in China (in the first six months of 2022, 27% more was added)

- total wind power capacity reached 329GW (including 26GW of offshore wind, mostly added in 2021)

- wind power accounted for roughly 13% of China's installed power capacity and 8% of China's electricity generation.

China has significant wind power resources, especially in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and other northern and western provinces and Chinese domestic firms dominate their wind turbine market.

Authorities in Shanghai recently unveiled plans to have 29.3GW of offshore wind capacity installed and feeding into its grid. The plan, formulated by the Shanghai Municipal Development and Reform Commission, aims to have offshore wind generating enough power for half of the huge city.

Offshore, China is already leading in installed wind capacity. At the end of 2022, the country had 31.4 GW installed, according to a report from Global Energy Monitor (GEM), and added a further 6.3 GW last year, for its sixth year in a row in the top position in newly installed capacities, according to Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC).

Wind farms will likely remain the most important source of renewable power in China for the foreseeable future, because of their ability to produce electricity even when the sun doesn't shine, and from diverse locations, often close to major demand centres.

Nuclear

China is also world leader in the deployment of new nuclear energy, benefitting from a low levelised cost of energy (LCOE), at US$70 per megawatt hour (MWh) (compare US$160/MWh in Europe and US$105/MWh in the US).

Latest assessments show China currently has 54GW of operable nuclear power reactors, with 31GW of nuclear power reactors under construction, another 45GW in planning and 98GW proposed as of February 2024, with more proposals for new nuclear reactors awaiting approval.

It is also forecast that China will double its nuclear power plant fleet to 108GW by 2040 to first in the world in terms of total installed capacity, overtaking the US at 100GW.

China's adoption of nuclear power dates back to 2011 when the country's National Energy Administration (NEA) announced China would make nuclear energy the foundation of its electricity generation system in the next "10 to 20 years," adding as much as 300GW of nuclear capacity over that period.

However, unusually China has delivered less than a sixth of this target, affected by the figurative fall-out from Fukushima meaning it limited itself to only installing the most modern facilities deploying the latest technology. Perhaps unsurprisingly they developed this technology themselves and became the world leader in this sector too.

December 2023 saw the world's first fourth generation nuclear power plant go into commercial operation, operated by Huaneng Shandong Shidao Bay Nuclear Power. The facility has a modest net capacity of 150MW, but still took a lengthy 11 years to construct after approval in 2012.

China's nuclear build is on accelerated upwards trajectory, leading to an estimate from the IEA that the real LCOE will fall 10% to US$65/MWh by 2050. This is at the same time as modelling shows the LCOE of coal with CCS will rise to US$220/MWh, three times the nuclear LCOE at 2050 and ten times the cost of solar.

The efficiencies of nuclear power at scale are clear to see - something which will have played into the decision made in August 2024 to build 11 more nuclear reactors across five sites in the provinces of Jiangsu, Shandong, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Guangxi.

With a total investment of 220bn yuan ($31bn), construction is expected to take approximately five years.

Solar

First some headlines:

- in 2023 China added 216.88GW of new PV capacity, up 148% from the 87.41 GW it added in 2022.

- according to the Global Energy Monitor, between March 2023 and March 2024, China installed more solar than it had in the previous three years combined, and more than the rest of the world combined for 2023.

- according to China's NEA, the country's cumulative PV capacity had reached 609.49GW at the end of 2023.

- in August 2024 research consultancy Rystad Energy predicted solar power would become China's primary source of electricity by 2026, after the combined capacity of the country's deployed solar and wind power overtook coal for the first time in June of that year.

So how has this dramatic change come about?

One factor is China's "Whole County PV" program which has dramatically expanded the use of solar power in rural areas, by building on government, commercial, industrial and residential rooftops.

China experiences much sunnier winters than most other countries. In Shandong, for example, a household solar panel might produce 76% as much electricity over the whole winter compared to summer – comparable to Phoenix, Arizona. Contrast that with London or Munich, where wintertime PV output will average only 20-25% of summer levels.

But until recently, most solar PV in China was installed in remote western regions, requiring costly transmission lines to bring the electricity to eastern provinces that use the most power.

A series of huge "clean energy bases" in desert regions continue to be an important part of the country's energy transition. Yet these large-scale, centralised developments have provided little low-carbon electricity to hundreds of millions of residents in rural areas.

The Whole County PV pilot program, initiated by China's energy regulator, the National Energy Administration (NEA), was developed to expand the use of distributed rooftop solar, including in rural communities.

A list of 676 participating counties and other administrative units – representing roughly half of China's county-level areas – was published and were called upon to add solar PV to 20% of residential rooftops, along with other targets for commercial, industrial and government rooftops.

The primary innovation of the program is reducing the costs of distributed solar – especially the soft costs of customer acquisition and contracting – via a tender or auction to select a single supplier and installer to cover all the rooftop installations included in each county pilot.

The program has already been credited with a dramatic increase in distributed solar since its launch. The National Development and the Reform Commission (NDRC), the planning body of the Chinese central government, has noted the program had more than 66 gigawatts (GW) of planned projects being registered by the end of 2022.

A more general challenge is integrating solar in rural areas, where excess peak PV output in midday could overwhelm local grids.

Geothermal

China has long been the world leader in the direct use of geothermal energy, with geothermal heating and cooling systems covering an area of 1.33 billion square meters. This is equivalent to an installed capacity of 92.4 gigawatts that can reduce over 60 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

Despite this, there are demands from within the country to speed up geological exploration and technological research to expand the use of the earth's heat.

Perhaps one reason for this is that among renewable energy sources, only geothermal energy is unaffected by natural conditions such as season and climate, and can provide uninterrupted power supply, with an annual rate several times higher than solar and wind energy.

While China has around one-sixth of the world's geothermal resources, the installed capacity of geothermal power in the country is lower than that of other renewable energy resources such as wind and solar, according to the World Geothermal Conference.

Sadly for China, the regions where most geothermal resources are very far from the economically developed coastal areas, where there demand lies, leading to increased costs.