Analysts at energy research company Wood Mackenzie expect natural gas to play a greater role in the energy transition than the International Energy Agency (IEA), which has arguably become a cheerleader for a net zero world that omits the economic and political realities in less developed economies.

Can the IEA no longer be trusted?

A recent commentary in the Wall Street Journal alluded that the IEA once provided solid information. However, as the author highlighted, its reports can no longer be trusted. Indeed, it's hard not to agree that today, "the IEA looks more like a climate-obsessed nongovernmental organisation."

"For most of the past five decades, the IEA fulfilled its watchdog duties. It became the gold standard for timely data, impartial analysis and forecasts devoid of political bias. The agency navigated energy crises, providing data and policy coordination during the two Gulf Wars, the 2019 Iranian attack on Saudi Arabia's Abqaiq oil facility, and various natural disasters affecting energy supply and basic energy trends," wrote Robert McNally, an energy consultant and author of "Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices."

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

"Unfortunately, in recent years, the IEA has succumbed to politicisation and strayed from its security mission. In 2020 the IEA bowed to enormous pressure from climate activists and ceased publication of oil and gas demand forecasts that didn't show demand for those fuels would soon peak because of imaginary future climate policies," added McNally, who also served as a special assistant to the president on the US National Economic Council, 2001-03.

It's not just McNally; many other energy industry professionals of every stripe have increasingly raised concerns about the IEA's impartiality in recent years.

Back in Asia gas demand is rising

Back in Asia, globally respected energy research company Wood Mackenzie is taking a more pragmatic approach to forecasting.

In a press briefing discussing Wood Mackenzie's latest outlook for the energy transition in APAC, Jom Madan, a senior analyst, said "we have a higher gas outlook (versus the IEA) because our view is a little bit nuanced. We view the transition as challenging, especially for the Asian region, where new infrastructure development is quite expensive."

For many countries in APAC, their main concern is affordability and supply security. "So in that case, we view gas as more resilient. Asia is going to use it as a springboard to transition later on, but just as an intermediate stopgap solution to reduce emissions," he added.

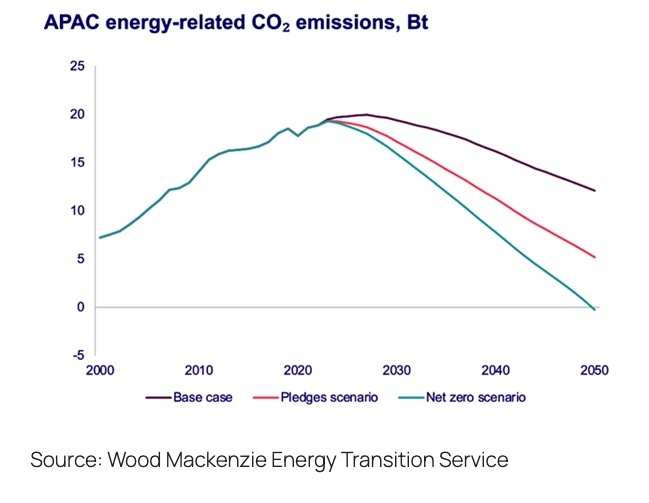

Prakash Sharma, vice president of scenarios and technologies research at Wood Mackenzie, underscored that the pace of the energy transition in APAC will be slower than widely expected, particularly compared to the IEA's scenarios. Many industry experts argue the IEA's energy outlooks are increasingly overly optimistic, especially where developing economies are concerned.

The energy research company says it is taking a more realistic approach to forecasting. Rather than working backwards from climate goals targeted in 2050, and considered as gospel, it has analysed the pace of the transition from the present, determining its base case outlook and potential net-zero scenarios.

Significantly, APAC is the world's largest market for oil, gas and coal. According to Wood Mackenzie, domestic production has historically fallen short of demand; this supply gap for oil and gas is expected to continue under all demand scenarios and will be met by imports. This should be good news for Australian exporters as there is a ready market for Australian commodities, including gas in the form of LNG, oil and coal, and emerging low-carbon fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia.

Energy juggernaut

"The Asia Pacific region is accounting for a third of global oil demand, a quarter of global gas demand, and 80% of global coal demand. But it doesn't produce enough to meet this demand on its own," said Roshna Nazar, a research analyst at the company.

According to Wood Mackenzie, gas demand will continue to increase for 15 years in all its scenarios, with growth in power and industry offsetting the long-term decline in buildings.

By 2050, gas demand is expected to grow from 890 billion cubic meters (bcm) to 1,285 bcm in the base case but fall to 655 bcm in the net zero scenario.

"Despite most of the Asia Pacific region being net importers of both oil and gas, domestic gas supply is declining in the region. It will require either new discoveries or liquefied natural gas (LNG). Even in the net zero scenario, substantial investment will be needed to maintain the supply from existing fields and develop new sources," Nazar added.

Significantly, LNG will continue to have a key role to play in the global energy transition, but only if the industry can decarbonise.

"Home to half of the world's population and contributing a third to the global GDP, the Asia Pacific region is expected to maintain a 50% share of global primary energy demand and a 60% share of global carbon emissions until 2050. This trend is unlikely to change without strong policy action and investment," noted Wood Mackenzie.

Pace of energy transition in APAC

Sharma told reporters that the pace of transition is extremely important because that determines the trajectory and the opportunity set for commodities and technologies.

While some industry proponents and forecasters look at what needs to happen in 2050, and then work backwards, Wood Mackenzie has an approach of starting from the current situation to calculate how quickly the pace of the transition and the pace of decarbonisation in different sectors and different markets can happen, he added.

"That is where we believe the impact on commodities will be somewhat different, especially in the near term, because the development of new supply, especially the low carbon supply, be it solar, wind, hydrogen or CCUS, will take a lot of time to develop," said Sharma.

"So that is why, in the near term, the pace of the transition will be somewhat subdued or slow. But then it can increase the pace, especially around post-2030. But that will be subject to the investment that goes into the sector. And that is why there are a number of different pathways," cautioned Sharma.

"And that requires us to do a different pace of the transition and different outlooks. So we have, as Jom mentioned, we have a base case view, which we believe is the most likely outcome given the current inertia in the energy system, given the current pace of capital allocation, but then the pace of the transition and decarbonisation can increase, especially around 2030, provided, the amount of investment that is needed takes place," he added.

Crucially, "every country in the Asia Pacific region is vastly different in terms of population growth, economic development, policy landscape, what natural resources they have and - more importantly - what they don't have will determine how they transition to a low-emissions pathway," said Sharma.

Energy security and the potential of renewable energy

Unfortunately, when the energy supply is constrained, everyone's bidding up prices. "We've seen in the past that the APAC region can't win the price war against Europe. So now policymakers are looking inward and seeing what they can do to become more self-reliant," noted Madan.

"The other obvious solution is to build more renewable energy to get away from the import dependence. Last year, China added 220 gigawatts of solar to its grid, more than the US has installed over its entire lifetime. Not everyone can do that," he added.

"Renewables are actually quite expensive because if your grid isn't prepared to take them, the more renewables you have, the more expensive it becomes. So, while China's building high voltage transmission lines crisscrossing the entire country, conversely Vietnam has been struggling with curtailment because its resources are in the south when the demand is in the north, and its transmission infrastructure can't handle it," said Madan.

Indeed, decarbonisation is confronting economic realities in Asia, but some forecasters, such as the IEA, appear to have missed that or prefer to omit them.

"Countries like Japan and Korea are without much domestic renewable energy potential, they are pushing for hydrogen heavily. For the less developed countries, even with much renewable potential, transmission infrastructure needs to be built out, and populations are still growing. Infrastructure is shoddy, with national coffers trimmed by COVID, making a challenging fiscal environment to pursue an expensive energy transition," warned Madan.

"That doesn't mean the transition isn't going to happen. For most of the region, policymakers have to zero down on solutions that make sense, solutions that are affordable," he added.

Hub of new energy technology opportunities

Importantly, APAC could become a global leader in the energy transition. In Wood Mackenzie's base case, low-carbon supply accounts for 35% of power generation today, and it's projected to rise to 75% by 2050, while the share of wind and solar increases to over 54%. China is set to achieve a cumulative solar and wind capacity of 2,000 GW by 2030, exceeding their target. By 2050, Australia is poised to lead the Asia Pacific region in renewable power generation, with a share of more than 80% in the base case and the scenarios.

This rapid growth in variable renewables is accompanied by the adoption of energy storage, hydrogen, small modular nuclear reactors, and geothermal technologies. By 2050, nearly 50% of the world's new technology opportunities for low carbon emissions will be in the Asia Pacific.

Hydrogen: Low-carbon hydrogen will reach 3.5% of final energy demand by 2050 in the base case and 12% in the net zero scenario, pushing out fossil fuels in chemicals, steel, cement and heavy-duty mobility.

Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS): In Wood Mackenzie's base case, point source and direct air carbon capture are expected to increase from 3 million tonnes in 2023 to 755 million tonnes by 2050. In the net zero case, the deployment will reach about 3,360 million tonnes by 2050. However, a significant expansion will be required to develop transport, shipping, and storage infrastructure to accommodate this increase.