When Thomas Edison unveiled the first commercially practical incandescent bulb in 1879, he sparked a revolution that lit the world and redefined how societies consumed energy. But it took more than a century before light-emitting diodes (LEDs) — vastly more efficient and durable — began to replace them at scale. The shift was not just technological – it propelled the world into the modern era.

Today, a new revolution in light may be unfolding. Laser-driven nuclear fusion — which replicates the same process that powers the stars — is edging closer to practicality. And just as dramatic gains in efficiency drove the incandescent-to-LED transition, the key to unlocking laser fusion's promise lies in one deceptively simple metric: how efficiently a laser converts electricity into light.

"The field is absolutely moving toward diode-pumped solid-state lasers," says Dr Warren McKenzie, co-founder of Sydney-based HB11 Energy and a materials scientist with a PhD and deep background in nanotechnology research.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

"That lifts wall-plug efficiency from less than 1% to about 10%— like replacing a tungsten filament with an LED."

That leap could define fusion's "lightbulb moment."

The sparkplug for the stars

Fusion's obsession with efficiency is more than academic. To fuse atoms, scientists must recreate the conditions found inside stars: crushing pressures and searing temperatures.

"Igniting a fusion burn is like lighting a damp log," McKenzie explains. "You need a spark plug that delivers a huge burst of energy to get it started. For us, that spark plug is the laser."

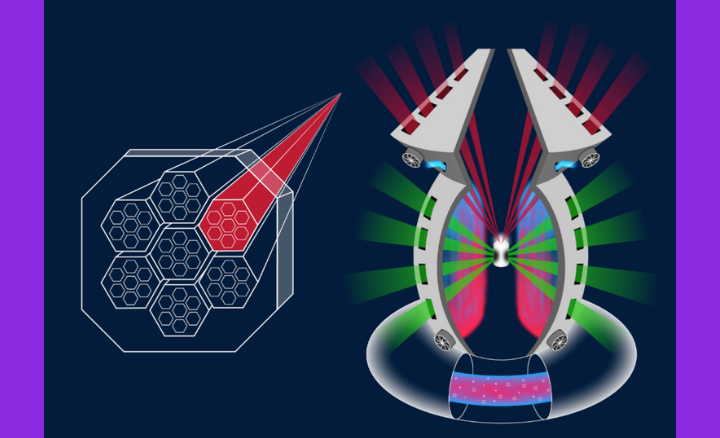

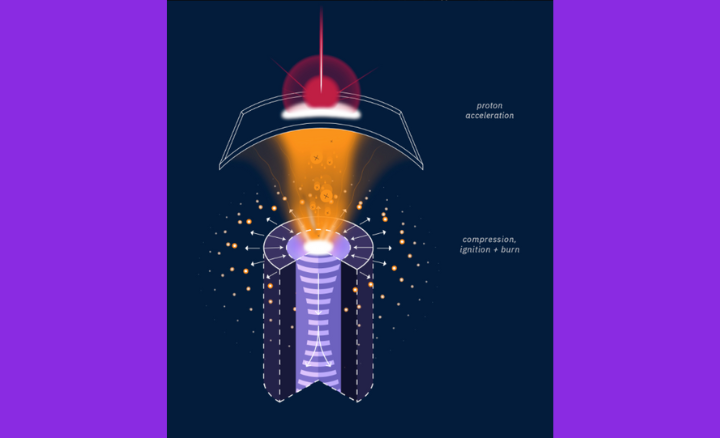

In inertial confinement fusion, high-powered lasers strike a tiny fuel pellet containing boron and hydrogen isotopes, squeezing it to a fraction of its original size. The brief moment of compression creates conditions hotter than the Sun's core — over 100 million degrees Celsius — allowing the nuclei to overcome their natural repulsion and fuse, releasing energy.

On Earth, however, there's no huge gravitational pressure to help out. Every joule of energy counts. The more efficient the laser, the closer fusion scientists get to the ultimate goal: producing more energy from fusion reactions than the system consumes — a state known as net gain.

That's why McKenzie and his team have been focusing on what he calls "incredibly energy-efficient lasers" — the sparkplugs of the future.

"We've got some big plans and progress for making them very high efficiency," he says. "We might have something to announce later in the year that's very newsworthy on that front."

From damp wood to plasma

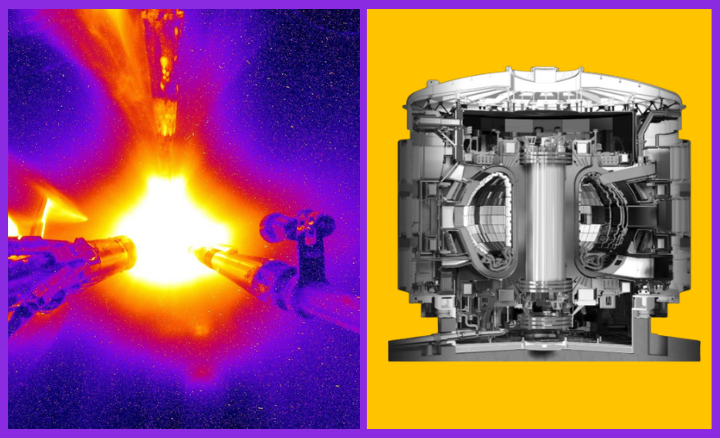

Laser fusion has achieved some impressive milestones. In late 2022, the US National Ignition Facility (NIF) reported the first-ever fusion experiment that produced more energy than the laser delivered to the target. The result made headlines, though McKenzie points out that the "engineering gain" — factoring in the vast energy losses within the laser system itself — remains negative.

HB11 – which spun out of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in 2019 – is trying to solve that problem differently in its pursuit of commercial fusion energy, where grid-scale production will be cheaper than fossil fuel sources available today. Its experiments focus on creating a more efficient pathway for fusion ignition, including using light, low-density materials.

The difficulty has been to develop a device that can heat the D-T fuel to a high enough temperature and confine it long enough so that more energy is released through fusion reactions than is used to get the reaction going – World Nuclear Association

These materials — foams just a few times denser than air — surround the fusion fuel, McKenzie explains.

"Shooting lasers into these materials form a what we call a non-critical density plasma — which is really important for commercial fusion energy," he says. "It is the most energy-efficient way to transform laser light into high-energy protons, which are what we actually need to ignite fusion."

The process begins when a laser pulse hits the low-density foam. The material ionises, creating a plasma and a cloud of accelerating high-energy protons that eventually slam into the fusion fuel, triggering reactions, reducing the level of ultra-high compression of other methods.

Building the perfect target

HB11's progress centres on these delicate, aerogel-like structures that serve as both target and catalyst. The company can now produce these materials in-house, which could give it a strategic edge as fusion research scales up.

"Our low-density foams are roughly ten times more efficient at proton acceleration," McKenzie says. "And we can now make them ourselves — a crucial step toward supplying the fuel targets future fusion power plants will need."

He believes this capability positions HB11 not just as a reactor designer but as a potential fuel supplier for the fusion industry.

"Achieving commercial fusion energy is all about efficiently turning electricity into light, then laser light into the high-energy particles needed to spark fusion," McKenzie says. "We're well advanced in developing these low-density foams that can be injected as part of the tiny fuel pellets for laser fusion."

The challenging road to commercial fusion

The fusion landscape is crowded — from the giant tokamaks of Europe's ITER project to America's privately funded startups. But HB11's pathway stands out for one simple reason: it includes boron in its fuel, which produces far fewer damaging and risky neutrons.

"It's not true there's no waste," McKenzie concedes. "But it's less — and even smaller with hydrogen–boron fusion."

That means the reactor walls won't suffer the same radiation damage that plagues fusion designs using pure deuterium–tritium. The result is lower maintenance costs and simpler construction.

"With hydrogen–boron, you can build the reactor vessel out of steel instead of tungsten," he says. "That's a massive cost advantage, and it could mean the first walls last the full plant lifetime, saving the need for their removal as radioactive waste before the plant is decommissioned.

A political hot potato

While the US, UK and EU pour billions into fusion through public–private partnerships and pro-growth regulation, Australia has yet to decide how the technology fits into its clean energy plans.

"In the US, fusion qualifies for clean energy tax credits," McKenzie says. "But here in Australia, it's a political hot potato because people think it might fall under the nuclear ban."

State and federal bans on nuclear power were designed for fission — the splitting of atoms — but their language can be ambiguous. HB11 and others argue that fusion isn't covered because it doesn't use fission fuels that produce chain reactions, long-lived radioactive waste, or meltdown risks.

"That ambiguity could cost our country dearly, McKenzie warns. "If we don't act, we won't be setting the price of energy anymore — we'll be accepting what someone else sells it to us for."

The race is on

Globally, investment in fusion has exploded. Private ventures now number more than 50, from Helion and Commonwealth Fusion Systems in the US to China's vast laser and tokamak programs.

"Hundreds of billions will flow into milestone-based public–private fusion partnerships as countries race to build the world's first fusion power plant," McKenzie predicts.

"Laser fusion has now reliably achieved a burning plasma and net energy gain, whereas magnetic fusion, despite enormous investment, hasn't yet."

For Australia, the race is both scientific and strategic. Fusion's energy density dwarfs renewables and fossil fuels alike — a single gram of hydrogen–boron fuel could, in theory, generate as much energy as tonnes of coal.

That promise hasn't escaped the attention of the oil and gas giants.

"They're not investing in fusion to control the supply," McKenzie says. "They're investing because they understand diversification. The only thing that could threaten an industry the size of oil and gas is fusion."

Waiting for ignition

The parallels between Edison's lightbulb and HB11's laser are remarkably precise. Both represent inflection points in how humanity controls energy — and both hinge on efficiency breakthroughs that make once-impractical technologies suddenly indispensable.

If HB11's "spark plug" lasers can turn light into fusion reactions with LED-like efficiency, the leap could be every bit as transformative as Edison's invention 146 years ago.

For now, McKenzie is keeping details close to his chest. But when asked about the coming announcement hinted at earlier, his tone shifts from scientific caution to quiet confidence.

"We've seen enough in the lab," he says, "to know that when that lightbulb moment comes, it's going to be bright."